Fancy bird; a Voorburg-Cropper Pigeon. Photo by Richard Bailey

Wild Thing

How and why did humans domesticate animals – and what might this tell us about the future of our own species?

One day in London in 1855, during an unusually cold winter, Charles Darwin went for a walk. As he strolled along the banks of the ice-bound Thames, he noticed some pigeons foraging for food. He began to wonder about their relationship to so-called ‘fancy pigeons’, the more exotic varieties favoured by fanciers and breeders. Was there an ancestor common to the nondescript blue-grey creatures on the riverbank, and those featured on the front page of Darwin’s newspaper that day, all puffed-up chests and improbable neck-ruffs?

AEON

Photo by Heidi Bradner

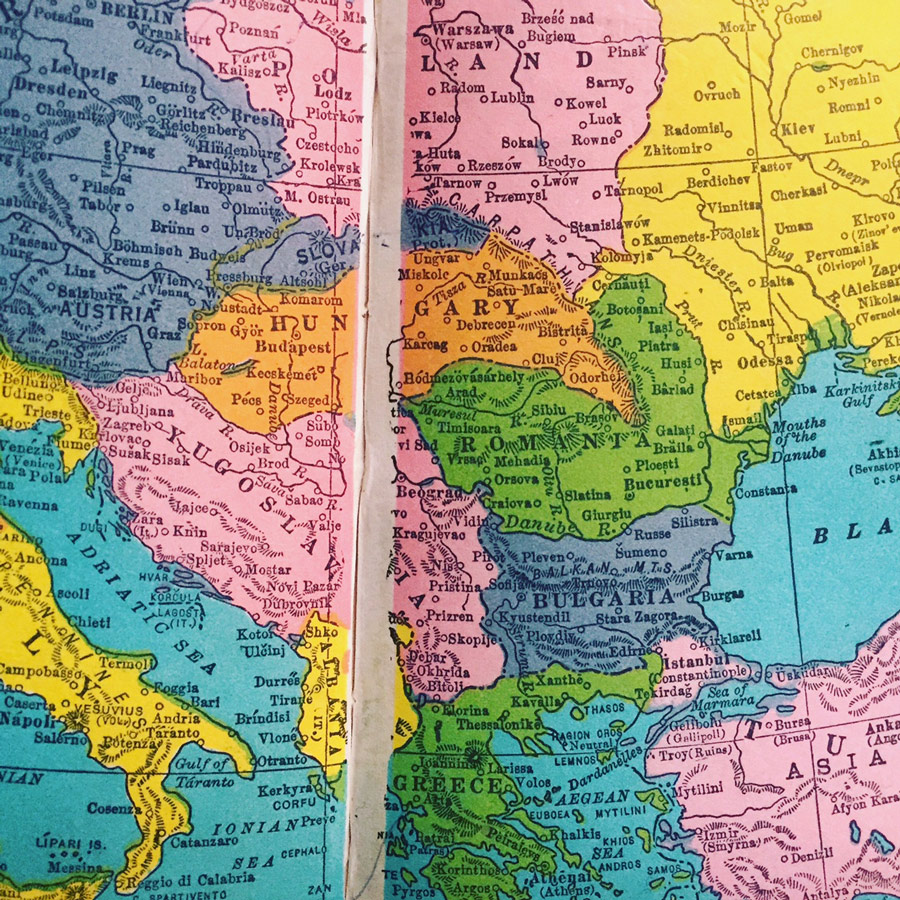

Origins

Paleogenetics is helping to solve the great mystery of prehistory: how did humans spread out over the earth?

Most of human history is prehistory. Of the 200,000 or more years that humans have spent on Earth, only a tiny fraction have been recorded in writing. Even in our own little sliver of geologic time, the 12,000 years of the Holocene, whose warm weather and relatively stable climate incubated the birth of agriculture, cities, states, and most of the other hallmarks of civilisation, writing has been more the exception than the rule...

AEON

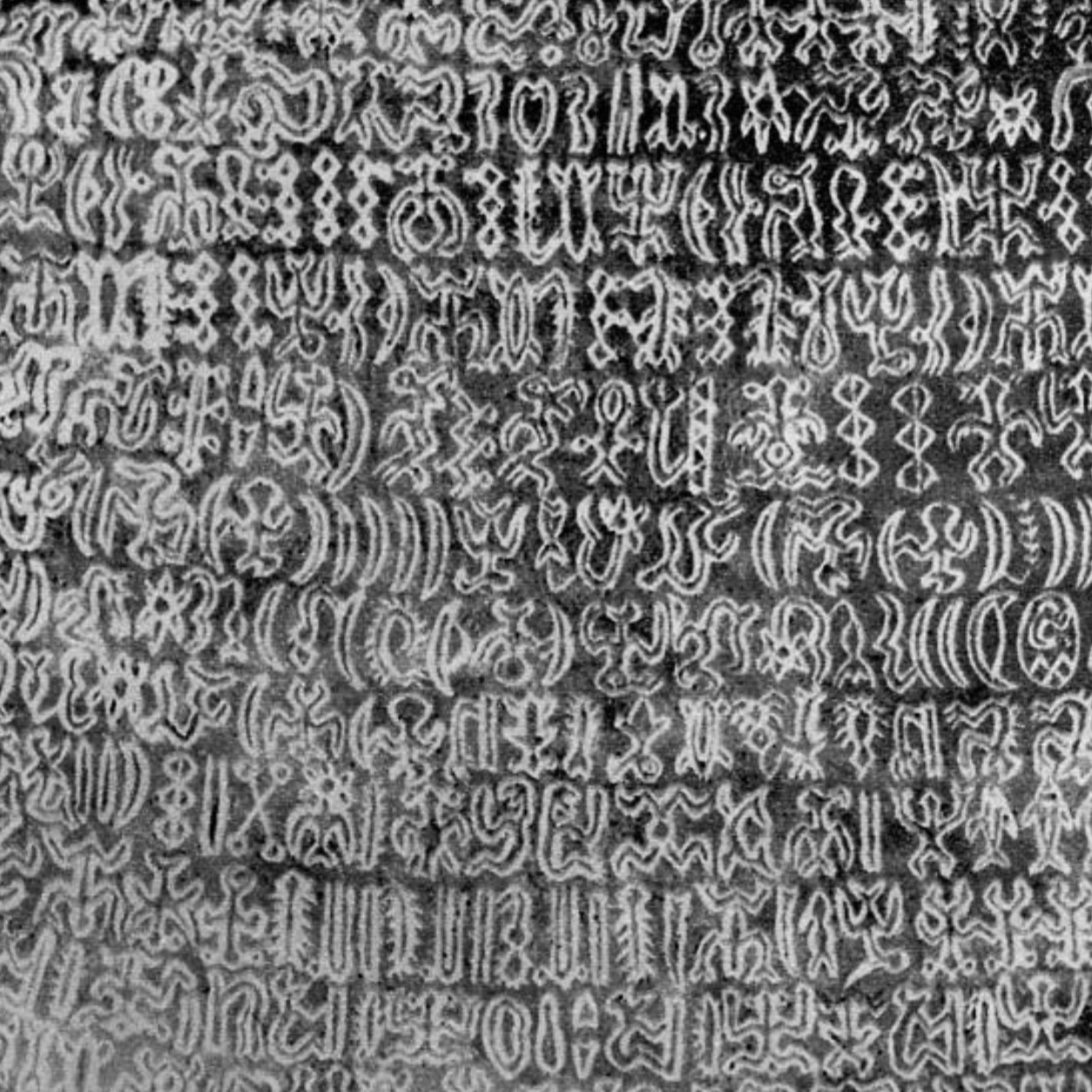

Monsters in the Museum

On February 13, 1718, Peter the Great, Tsar of all the Russias, issued an edict on monsters: All monsters, animal or human, were to be requisitioned for the new museum in his new city, St. Petersburg. Peter desired anything in the realm that was marvelous—extraordinary stones, human and animal skeletons, the bones of fish and birds, old inscriptions, ancient coins, hidden artifacts, old and remarkable weapons—but he wanted monsters most of all.

Monsters, Peter believed, were not the work of the devil, but products of nature. He offered generous payment: Delivery of live specimens would fetch a hundred rubles for humans, fifteen for animals, and seven for birds. Dead ones, preserved in spirits, or, failing that...

THE AWL

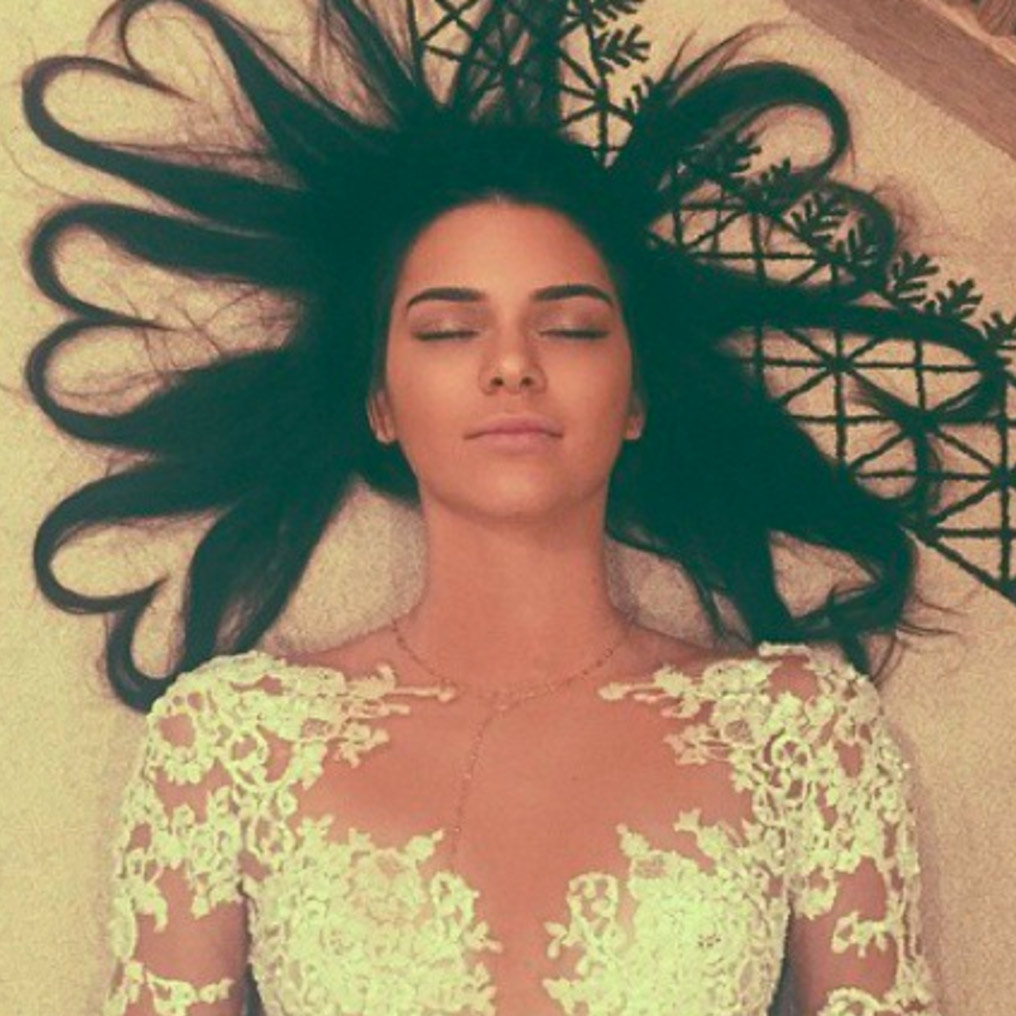

For a long time, this was the most popular picture on Instagram. If the photograph has a single antecedent, it is John Everett Millais’ painting of Ophelia from 1852. It combines the coiffure of Florentine princesses with the quintessential pose of tragic womanhood from the Victorian era. The cherry on top is the caption: a single, sideways glyph of a heart.

Camera-phone Lucida

The historical roots of our instagram obsession

Facebook is Sauron. It’s also your mom’s couch, a yoga-center bulletin board, a school bus, a television tuned to every channel. Twitter is Grub Street, a press scrum, the crowd in front of a bar. Reddit is a tin-foil hat and a sewer. Snapchat is hover boards, Rock ’em Sock ’em Robots and Saturday morning cartoons. Instagram is a garden: curated, pruned, clean and pretty. It lets you be creative, but not too creative; communicate, but without saying too much. No embedding, no links—just photos, captions and hashtags. Elegant. Simple. Twenty-three filters. A crisp square around each frame...

THE POINT

Sight Beyond Sight, Carleton Watkins' California

How one pioneering photographer captured the American West before its ruin—and before his own.

Watkins came to the state in 1851 during the Gold Rush, and photographed California as if it were a new planet on which he was the first person to arrive.

PACIFIC STANDARD

Yosemite, California

Carleton Watkins: Yosemite, California